AHRQ White Papers on Health IT, Patient Involvement, and Beahvioral Health

In Patient Centered Medical Home Environment

Excerpts from Health IT White Paper

On July 22, 2010, AHRQ announced “the launch of a new Website [ http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov ] devoted to providing objective information to policymakers and researchers on the medical home. The site provides users with searchable access to a rich database of publications and other resources on the medical home and exclusive access to the following AHRQ-funded white papers focused on critical medical home issues:”

Three New AHRQ Commissioned Research White Papers Featured

- Health IT Paper:

“Necessary, but not sufficient: The HITECH Act’s Potential to Build Medical Homes” The recent Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) legislation for adoption of health information technology (IT) in public insurance programs could be harnessed to help practices operationalize and implement the technology and supports key principles of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) to improve health care quality and efficiency. While HITECH, as well as aspects of recently enacted health reform legislation, support many facets of the PCMH model, these provisions are not likely to be sufficient to drive wholesale primary care transformation. Three policy recommendations—developing PCMH-specific certification criteria for electronic health records; including PCMH functionalities in the meaningful-use concept; and extending the role of HITECH’s Regional Extension Centers to provide technical assistance to primary care providers on medical home principles—would increase the ability of health IT to support transformation by primary care practices to the PCMH model.

(PDF – 236KB) Excerpts below.

- Patient Involvement Paper:

“Engaging Patients and Families in the Medical Home” The PCMH model provides multiple opportunities to engage patients and families within the health care system, in care for the individual patient, in practice improvement, and in policy design and implementation. This paper presents researchers and policymakers with a framework for conceptualizing these opportunities and provides insight into the evidence base for these activities, describes existing efforts, suggests key lessons for future efforts, and discusses implications for policy and research.

(PDF – 571KB)

- Behavioral Health Paper:

“Integrating Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment in the Patient-Centered Medical Home” Given that primary care serves as a main venue for providing mental health treatment, it is important to consider whether the adoption of the PCMH model is conducive to delivery of such treatment. This paper identifies the conceptual similarities and differences between the PCMH and current strategies used to deliver mental health treatment in primary care. Even though adoption of the PCMH has the potential to enhance delivery of mental health treatment in primary care, several programmatic and policy actions are needed to integrate high-quality mental health treatment within a PCMH(PDF – 175KB)

Health IT Paper:

“Necessary, but not sufficient: The HITECH Act’s Potential to Build Medical Homes”

Full PDF Version

Report was produced for AHRQ by Mathematica Policy Research, Washington, DC, and written by Lorenzo Moreno, Ph.D.; Deborah Peikes, Ph.D.; and Amy Krilla, M.S.W. and published July 2010. Excerpts from the report

Introduction

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a promising model of care that aims to strengthen the primary care foundation of the health care system by reorganizing the way primary care practices provide care. Rapidly emerging interest in the PCMH model reflects a growing recognition that the U.S. health care system has become highly fragmented, with advances in medical technology and increased specialization leading to an erosion of primary care and care coordination. In addition, recent evidence shows that areas with fewer primary care providers are plagued by higher health care costs and, perversely, lower-quality care.Furthermore, low payment for primary care, together with the heavy demands on its workforce, are leading fewer medical school residents to select primary care. Policymakers and others hope that reorganizing primary care into medical homes and increasing payments will help rebalance the system and reconfigure it in ways that improve patient and provider satisfaction, control costs, and improve quality. Stakeholders, including Federal and State agencies, insurers, providers, employers, and patient advocacy organizations, are striving to refashion the landscape of primary care in this country through medical home demonstrations and pilots.

Adoption of the PCMH model calls for fundamental changes in the way many primary care ractices operate, including adoption of health information technology (IT) both for internal rocesses and for connecting the practice with its patients and with other providers. Health IT has been promoted as a “disruptive innovation” that offers tremendous promise for transforming health care delivery systems, including primary care. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) allocated $19.2 billion to promote the adoption of use of health IT by eligible providers who serve patients covered by Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, the use of technology is rewarded, and in some cases required, for primary care practices to qualify to be medical homes for both public and private initiatives.30-32 As substantial investments are being made to advance both the medical home model and IT adoption, understanding how best to promote adoption of health IT in a way that fosters improved primary care delivery is important. The first half of this paper discusses the potential role the HITECH Act in general, and health IT in particular, can play in improving primary care through support of the PCMH model. It does not assess whether the PCMH or health IT can improve quality and reduce costs. The first half describes (1) the medical home model; (2) examines how health IT can support specific features of the medical home model for providers and potentially improve patient care; and (3) highlights the barriers and facilitators to health IT adoption and improved delivery of care by primary care practices as revealed in the literature. The second half of the paper describes how the HITECH programs, as well as other related legislation, may address these barriers and ways they may need to be supplemented to better support practices as they seek to provide improved primary care.

How Health IT Might Support Primary Care Practices Acting as Medical Homes

Although providers could implement the PCMH model without health IT, this technology can be a strong facilitator to the establishment of this model of care, as demonstrated by growing evidence of the impacts of health IT on quality of care.33 However, it remains unclear how health IT will contribute in practice to enabling operation as a medical home.

Available evidence on the ability of health IT to support the medical home is mixed. Some evidence suggests that it improves the cost-effectiveness, efficiency, quality, and safety of medical care delivery, although there is not yet strong, broad evidence of success.35-37 Critics of health IT, however, argue that “if you computerize an inefficient system, you will simply make it inefficient, faster,” and have warned proponents of this technology to resist “magical thinking”—that is, the belief that health IT alone will positively transform primary care delivery systems.

To avoid these pitfalls, experts have argued that, rather than identify health IT as a solution to the problem of transforming practices into medical homes, a more realistic and fruitful approach is to identify the specific health IT capabilities that could help practices become successful medical homes.

Among the different IT applications for health care, policy experts envision electronic health record (EHR) systems as the cornerstone of health care transformation. These systems vary widely on the functionalities they offer, as well as across care settings and the provider’s specialties. An EHR system typically consists of the following four sets of functionalities (and subfunctionalities):

• Electronic Clinical Documentation: patient demographics, provider notes, nursing assessments, problem lists, medication lists, discharge summaries, and advanced directives

• Results to View: laboratory reports, radiology reports, radiology images, and consultant reports

• Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE): laboratory tests, radiology tests, medications, consultation requests, and nursing orders

• Decision Support: clinical guidelines, clinical reminders, drug-allergy alerts, drug-drug interactions alerts, drug-laboratory interactions alert, and drug dosing support

As the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services defines it, a basic EHR system includes only electronic clinical documentation (except advance directives); viewing of laboratory and radiology reports, and of test results; and medication CPOE. In contrast, a comprehensive EHR system includes all the functionalities and subfunctionalities listed above. These definitions are likely to change soon as recent health IT rules on the use of EHRs, certification, and standards are finalized. Likewise, as the functional model for EHRs evolves from an integrated, standalone system to modular functionalities for PCs, Web-based systems, and smart phones, the typology above could become irrelevant.

The appropriate use of two other technologies could also help transform health care. First, personal health records (PHRs), which are owned by the patient, typically document electronically (1) health and demographic information, including medical and behavioral health contacts and health insurance information; (2) drug information; (3) family health history; (4) a patient diary or journal; and (5) documents and images. PHRs are the patient counterpart to EHRs, although EHRs are far more common right now and are receiving the bulk of attention from Federal and State government, as well as the private sector. If adopted more broadly, PHRs have the potential to help primary care providers empower patients, and enhance the continuity of care provided, important determinants of health care transformation.

Second, telemedicine systems typically include the following functionalities: (1) remote clinical monitoring; (2) videoconferencing; (3) Web-based educational materials; (4) chat rooms; and (5) patient-provider communications in an integrated and secure environment. The use of this technology for patient care is growing rapidly as a viable option to improve access to care for patients who live in remote areas or are institutionalized, as well as to deliver confidential services, such as mental health care. Telemedicine also is gaining traction in Federal and State government, and in the private sector. This technology can make appropriate health care more accessible. Presumably, the content of care provided through telemedicine, as well as more traditional means, would be documented in the EHR, enhancing its value.

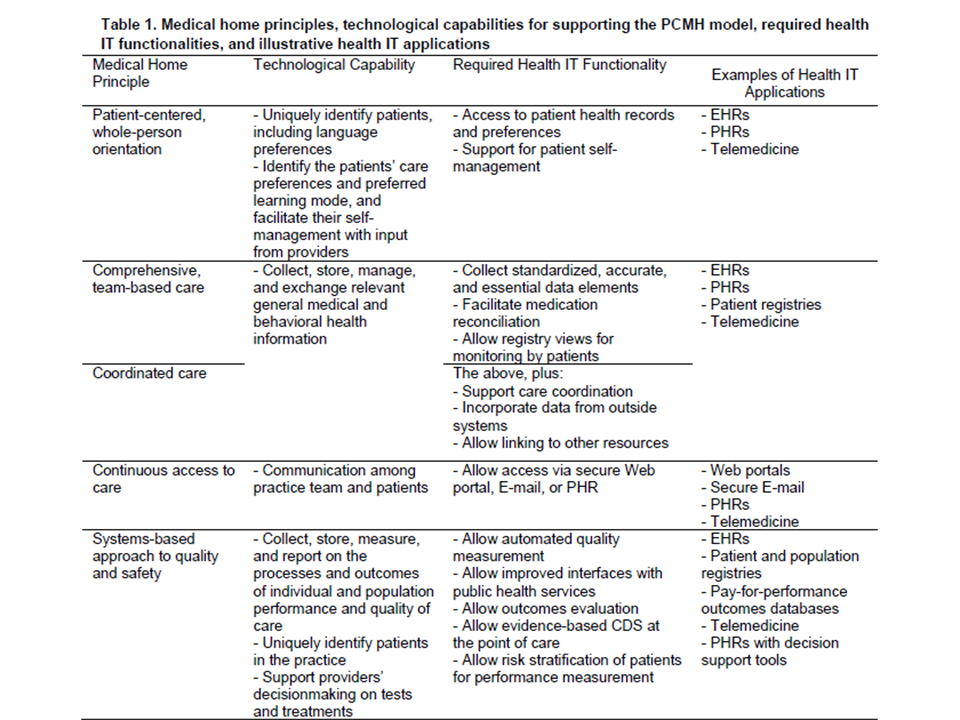

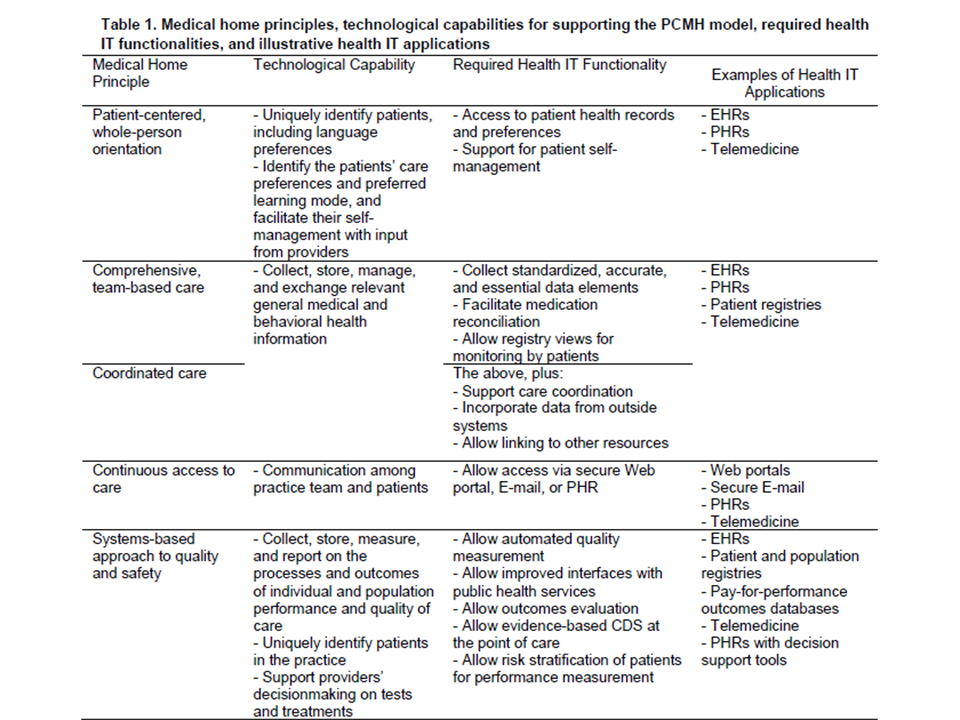

Experts in the development of the PCMH model have identified five capabilities that health IT in general, and EHRs in particular, would need to have to support the PCMH model: (1) collect, store, manage, and exchange relevant personal health information; (2) allow communication among providers, patients, and the patients’ care teams for care delivery and care management; (3) collect, store, measure, and report on the processes and outcomes of individual and population performance and quality of care; (4) support providers’ decisionmaking on tests and treatments; and (5) inform patients about their health and medical conditions, and facilitate their self-management with input from providers. Table 1 shows a crosswalk of the five medical home principles, the technological capabilities, the general functionalities required of the technology, and an illustrative list of the applications capable of supporting the PCMH model.

Table 1: Medical Home Principles

Source: Mathematica’s adaptation from the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, 2009, pp. 7-14.

Key: CDS = clinical decision support; EHR = electronic health record; PHR = personal health record.

In sum, comprehensive EHRs, and to a lesser extent basic EHRs, can support the medical home in important ways. Likewise, PHRs can support all five medical home principles, though given the Federal Government’s overwhelming focus on EHRs, this technology is unlikely to reach widespread dissemination and acceptance soon. Other, less-sophisticated technologies, such as patient population registries, can also address some of the medical home principles at relatively low cost. Thus, the question is how practices are currently implementing health IT, and particularly EHRs, so policymakers can better understand what support practices need to ensure that it contributes to the PCMH.

Conclusions

Discussion

HITECH has the potential to contribute to “cohesive, broad-based policy changes . . . that could lead to improved absolute and relative performance,” including the transformation practices need to act as PCMHs.90 While HITECH programs and other Federal legislation are necessary, they are not sufficient factors for providers considering the adoption of the PCMH model. As noted by a panel of experts consulted for this project, HITECH’s funding is not enough to support adoption and meaningful use of EHRs, let alone the broader transformation in care delivery needed to build PCMH. Other funding sources will be needed. Thus, although meaningful use of EHRs and other HITECH programs may contribute greatly to the adoption of a PCMH model, it seems clear that other factors beyond meaningful use are needed to attain this model of care, such as reform of systems for health delivery and health provider payment. In particular, reform of the latter would align the incentives of the PCMH model to increase accountability for total costs across the continuum of care, most notably between primary care providers and specialists, a feature conspicuously absent in the meaningful-use policy priorities. As one expert noted at the technical expert panel meeting January 15, 2010, “Absent provider payment reform, HITECH will not, by itself, stimulate the widespread formation of medical homes.” An assessment of the effectiveness of HITECH will not be possible before the second half of this decade. Because the legislation is just being implemented, evidence about the likely success of implementation of the HITECH’s programs and, in particular, of the meaningful-use concept and its role in promoting the PCMH model, is limited to a few studies, such as CMS’s Medicare Care Management Performance (MCMP) Demonstration and Electronic Health Records Demonstration (EHRD).91,92 These two demonstrations are testing the impact of financial incentives on the adoption and use of EHRs and on quality of care. Although they were not set up to test the meaningful-use concept or the medical home model, they will measure the actual use of EHRs with a survey of office systems. Furthermore, the interventions both target small to medium-sized practices serving Medicare beneficiaries with certain chronic conditions, similar to the settings targeted by HITECH. For these reasons, findings from these demonstrations offer the best opportunity for obtaining an early glimpse of the implementation of the meaningful-use concept in Medicare and of the barriers and facilitators to attaining meaningful use of the technology in medical homes. However, only findings from MCMP will be available by 2011, the first year of implementation of the meaningful-use concept; findings from EHRD are expected in 2015.

Although this paper focuses on the intended consequences of HITECH programs on the adoption of health IT and medical homes by primary care practices, unintended consequences also matter. For example, linking provider reimbursement to meaningful use of EHRs, with the consequent increases in financial and staff costs, may unwittingly slow PCMH adoption if practices focus exclusively on EHR adoption and not on other components of improved primary care. Likewise, the EHR Incentive Program could crowd out some private investment by practices who would have used their own resources to adopt EHRs. In addition, the resources (in both money and time) needed to implement EHRs might supplant resources that could otherwise have been directed at quality improvement. Finally, emphasizing health IT as the solution to physician practice problems stemming from poor organization or suboptimal care processes may result merely in greater investment in ineffective changes. Table 4 highlights these and other unintended consequences. Given the broad nature of the systemic changes proposed by HITECH and other legislation, it may take 5 to 10 years to figure out the full unintended effects of health IT on transforming practices into medical homes.

For the complete PDF of the report, click here.

See a later e-Healthcare Marketing post on an AHRQ White Paper, Practice-Based Population Health: Information Technology to Support Transformation to Proactive Primary Care.