New Practice-Based Population Health Report Now Available

AHRQ released a new research paper, Practice-Based Population Health: Information Technology to Support Transformation to Proactive Primary Care, announced via email on August 4, 2010, and posted the report on its PCMH (Patient-Centered Medical Home) Resource Center. The paper ”focuses on the concept of practice-based population health (PBPH),” and “examines the potential benefit of greater adoption of PBPH as well as the challenges to adoption by the primary care community.” Select to access the report.

The paper was prepared by NORC at the University of Chicago, and was authored by Caitlin M. Cusack, MD, MPH; Alana D. Knudson, PhD, EdM; Jessica L. Kronstadt, MPP; Rachedl F. Singer, PhD, MPH, MPA; and Alexa L. Brown, BS. It holds a July 2010 publication date.3

Summary from PCMH Resource Center (AHRQ-Commissioned Research)

Practice-Based Population Health: Information Technology to Support Transformation to Proactive Primary Care. “This report describes the concept of Practice-Based Population Health as an approach to care that uses information on a group (“population”) of patients within a primary care practice or group of practices (“practice-based”) to improve the care and clinical outcomes of patients within that practice. It also discusses the information management functionalities that may help primary care practices to move forward with this type of proactive management as well as the relationship between these functionalities and health IT certification efforts, proposed objectives for electronic health record incentive programs, and the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.” (PDF – 236KB)

Practice-Based Population Health: Information Technology to Support Transformation to Proactive Primary Care.

Excerpts selected on 8/6/2010. Sections or chapters should only be considered excerpts and may not include complete sections or chapters. PDF also contains charts.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The transformation of primary care is a key component of current efforts to improve health care in the United States and of the policy debate on national health care reform. The proactive measurement and management of the panel of patients in an individual practice may be one aspect of that transformation. This approach to care and the concept we developed to characterize its core—Practice-Based Population Health (PBPH)—are the focus of the project presented here.

We define PBPH as an approach to care that uses information on a group (“population”) of patients within a primary care practice or group of practices (“practice-based”) to improve the care and clinical outcomes of patients within that practice. With funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago has identified the functionalities necessary to more effectively prevent disease and manage chronic conditions using a PBPH approach. By helping providers focus on the preventive care needs of all of their patients, including those individuals who do not appear in the office for routine care, PBPH can help practices conduct more comprehensive health promotion and disease management. PBPH can also be used to serve a variety of other purposes—for example, to develop lists of patients to invite to a group educational session on smoking cessation or chronic disease self-management; to identify patients to notify in the case of a medication recall; to find patients who are eligible for participation in clinical trials; and to make informed decisions about areas for continuing medical education.

Information Management Functionalities for Practice-Based Population Health

To further develop the concept of PBPH, the project team developed and vetted a series of information management functionalities to support proactive population management. The list was refined through discussions with a group of experts and a series of interviews with primary care providers and office staff. The functionalities were grouped into the following five domains:

Domain 1: Identify Subpopulations of Patients. Practices can target patients who require preventive care or tests.

Domain 2: Examine Detailed Characteristics of Identified Subpopulations. Information management systems can allow practices to run queries to narrow down the subpopulation of patients or to access patient records or additional patient information.

Domain 3: Create Reminders for Patients and Providers. Information on patients can be made actionable through notifications for patients and members of the practice.

Domain 4: Track Performance Measures. Practices can gain an understanding of how they are providing care relative to national guidelines or peer comparison groups.

Domain 5: Make Data Available in Multiple Forms. Information may be most useful to practices if it can be printed, saved, or exported and if it can be displayed graphically.

Challenges to Adoption of Practice-Based Population Health

During our interviews with providers, we found that practices with electronic health records (EHRs) and registries are performing more of the PBPH functionalities than are paper-based practices, but none of the practices is performing all of the functionalities. More widespread adoption of PBPH will require technological innovations; greater availability of usable data; new methods for reimbursement of primary care; and changes in physicians’ views of care delivery and their practice workflow.

Having access to an EHR or a registry increases the likelihood that practices are performing these functionalities, but such access is not sufficient for the adoption of PBPH. For systems to facilitate population management, they need to be user-friendly and contain robust PBPH capabilities. Several of the 27 providers we interviewed said either that they were unable to find systems that include population management functionalities or that the products they had purchased are not living up to their expectations in performing these management tasks.

However, most providers are not actively seeking the tools needed for PBPH. With this lack of provider demand there is little incentive for vendors to create tools to support these functionalities.

To engage in PBPH, practices need accurate data in a discrete form. Providers we interviewed explained they often are able to run queries only on billing data, which may be inaccurate and insufficient for supporting PBPH. Practices also need to access patient information that is generated from other parts of the health care system, such as laboratory and pharmacy data. Additionally, for performance reporting, many providers feel that systems need to accommodate exception codes, so that patients who have refused treatment or patients for whom a particular treatment is inappropriate because of their comorbidities can be excluded from calculations of performance measures.

Because clinicians are trained to provide individualized care to one patient at a time, changing providers’ focus to the population level will require a paradigm shift. The clinicians we interviewed were also concerned with the disruption of workflow that PBPH could cause because of the time needed to collect and analyze data on the patient population and the increased need for appointments that more proactive care requires.

The providers we interviewed also expressed concern that the current reimbursement system would not cover the costs of more proactive management and coordination of care. Practices are currently using PBPH in limited instances where funding is available through grant programs or insurer incentives that target improved management of particular conditions.

Leveraging Policies to Address Challenges and Next Steps

The movement toward health care reform and unprecedented Federal investment in health information technology (IT) provide a window of opportunity for transforming primary care. To increase the adoption of PBPH, incentives for proactive population management can be incorporated into policies related to provider payment, the health-IT-related economic stimulus provisions in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), and efforts to strengthen the primary care workforce. Further research and dissemination could also increase appreciation of the potential of PBPH and support broader adoption of this approach to care.

Proposed efforts to reform the health care system may provide opportunities to change the reimbursement structure for primary care. Reimbursement with a greater emphasis on outcomes could provide additional resources and incentives for primary care practices to engage in PBPH. Increased provider demand would probably motivate IT vendors to develop applications that support population management. Health care reform may also support models like the patientcentered medical home, of which PBPH is a component. Another opportunity presented by health reform is that it may lead to a uniform set of performance measures, which would make it easier for vendors to develop products that address PBPH and meet the needs of primary care practices.

Incentives to Medicare and Medicaid providers who demonstrate “meaningful use” of EHRs, which were introduced in ARRA, are likely to boost health IT adoption. PBPH could most directly be supported by this legislation if PBPH functionalities are incorporated into those criteria. ARRA could also increase the amount of information available in electronic form by boosting EHR adoption and health information exchange nationwide. Finally, the ARRA-funded extension centers could provide training to help providers engage in PBPH.

In addition to assistance in using technology, physicians, nurses, and others in the primary care workforce may require additional training to be able to interpret reports on their patient populations. Medical and nursing schools could also support the advancement of PBPH, by helping providers adopt a more population-focused orientation.

Further research may also be important in fostering PBPH. To make population management tools more useful to primary care providers, research could be conducted to advance learning in a number of critical areas—how to automate preventive care or disease management services; to improve natural language processing for converting text into discrete data elements in real time; to effectively use “messy” data in practice; to develop case studies of best practices in PBPH; and to compile specific data elements for PBPH tools.

To translate this project’s findings into practice and, ultimately, influence and advance the transformation of primary care delivery, the concept of PBPH must first be introduced among primary care providers, health IT vendors, educators, policymakers, and third-party payers.

Second, the functionalities required for optimal implementation of PBPH need further vetting and refinement among primary care providers and health IT vendors, which could include adding additional technical specifications. Third, educators need to be acquainted with PBPH concepts in order to develop PBPH education and training that incorporates the use of PBPH in primary care practice.

As training and technology to support population management become more available and incentives are established to foster this type of care, PBPH may become a viable option for primary care providers. Such advances will help PBPH contribute to transforming primary care and to improving health care quality, patient health, provider satisfaction, and the efficiency of the health care system.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

The transformation of primary care is a key component of current efforts to improve health care in the United States and of the policy debate on national health care reform. Motivation to change the current primary care system stems, in part, from frustration by what Morrison and Smith have called the “hamster health care” model of care.1 This model is characterized by overloaded primary care practices, fee-for-service reimbursement which pays for acute care services rather than chronic condition management, and the “persistent presence of the ‘tyranny of the urgent’ in everyday practice.”2 These factors often combine to create a style and pace of practice that is a threat to quality of care, as it neither adequately assesses nor systematically improves the health of the population, or panel, of patients seen by a provider.

A key aspect of primary care transformation is the proactive management of a panel of patients within an individual practice. The project presented here focused on this facet of transformation and introduced a concept to characterize its core—Practice-Based Population Health (PBPH). We define PBPH as an approach to care that uses information on a group (“population”) of patients within a primary care practice or group of practices (“practice-based”) to improve the care and clinical outcomes of patients within that practice.

This report describes the concept of PBPH and the information management functionalities that may help primary care practices to move forward with this type of proactive management. With funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago has identified the functionalities necessary to more effectively prevent disease and manage chronic conditions using a PBPH approach. Specifically, through consultation with primary care providers and an expert panel, we have developed and vetted a list of functionalities to support the PBPH approach to care. While this project focused primarily on the information management functionalities that may help primary care practices proactively manage their patient populations, we note that there are a number of other factors important to facilitating this type of care, most notably the need for changes in workflow and new reimbursement models.4 Tackling these issues will be necessary for the widespread adoption of PBPH, and this report briefly addresses them in the next steps section.

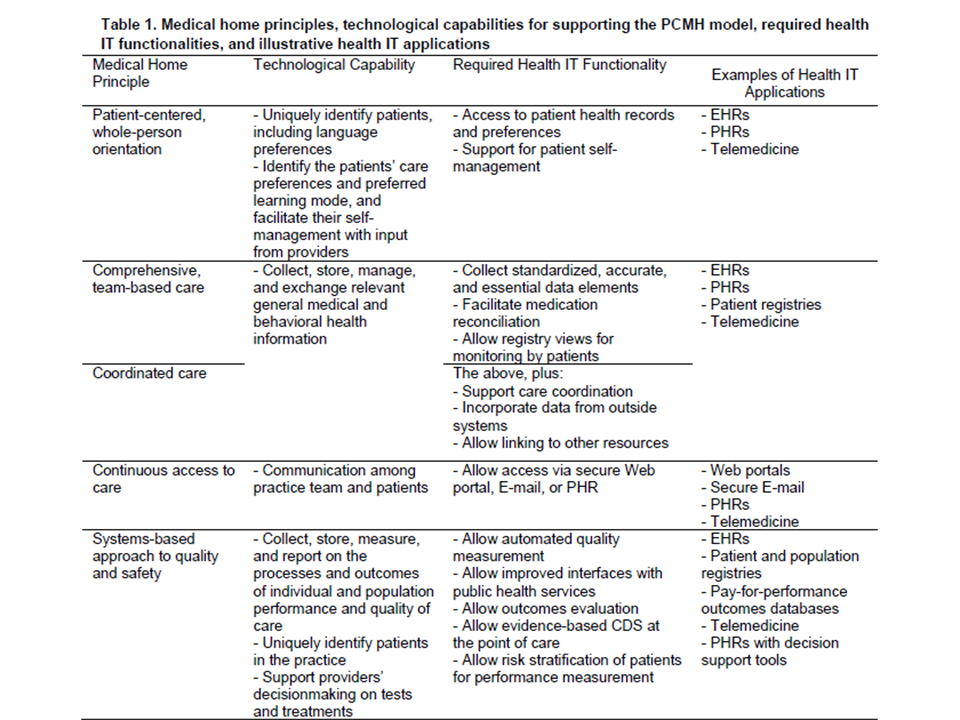

This report begins with a discussion of the methodology employed in the project and an explanation of the project’s scope. It then provides a definition of PBPH and a description of its key elements. We present the set of functionalities that was developed and refined as part of this project. We describe how the providers we interviewed are engaging in population management in their practices, and include providers’ views on the importance of the functionalities and their ability to perform them. To place the functionalities in a broader context, we discuss the relationship between these functionalities and health information technology (IT) certification efforts, proposed objectives for electronic health record (EHR) incentive programs, and the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model. Our research suggests that proactive population management is relatively rare and thus we discuss some of the challenges to adopting a PBPH approach, as well as a series of recommendations from our project’s experts on how to incorporate PBPH into current policy efforts and specific research and dissemination steps that would serve to foster PBPH. The report concludes with a series of examples, identified through an environmental scan, to illustrate how primary care providers are engaging in some elements of population management.

CHAPTER 2: PROJECT METHODOLOGY

With this project, AHRQ sought to build on earlier work done by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). According to the 2007 IHI report, Health Information Technology for Improving Quality of Care in Primary Care Settings, health IT may improve primary care through: (1) direct benefits, such as operational efficiency and safety achieved by reduction of administrative or clinical errors; and (2) improvements to the system of care, such as proactive planning for population care and whole patient view for planned care. IHI focused on the second area—systems improvements—and our work on this project continued that focus. We incorporated elements from the recommendations of the IHI report into our initial list of functionalities, which were then refined, as described later in this chapter. This project also expanded on the IHI report by seeking additional examples of the approaches primary care practices are taking to incorporate health IT into population health management.

To develop the concept of Practice-Based Population Health (PBPH) and the functionalities to support it, we conducted an environmental scan, convened a group of expert advisors, and conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with primary care providers and office staff.

CHAPTER 7: CHALLENGES AND NEXT STEPS

Although our interviews and environmental scan identified several examples of primary care practices engaging in proactive population management, there are a number of barriers to its widespread adoption. This section highlights some of the challenges that primary care practices and individual providers face in implementing PBPH. It also includes recommendations from our experts for promoting a population health management approach to primary care.

Challenges to Adoption of PBPH

Through our discussions with providers and other office staff, as well as input from the experts, we identified some of the major barriers to the adoption of PBPH. There are challenges related to both technology and data that need to be overcome. In addition, changes in reimbursement may be needed to support this paradigm. Lastly, a shift in physicians’ views of care delivery and their workflow may be necessary.

Adopting either a registry or an EHR may be necessary to support the engagement of a primary care practice in PBPH. However, it is important to acknowledge that at this point, adoption of this technology is far from universal. In 2006, just below 30 percent of office-based physicians reported using full or partial EHR systems, with use increasing with the number of physicians in the practice. Registries may also be more common among larger practices, but one national survey of practices with 20 or more physicians found that fewer than half (47 percent) had a registry for at least one chronic disease.

There are many explanations for the slow adoption of EHRs. In our interviews, providers discussed some of the reasons they have not implemented EHRs including the purchase cost, training expenses, productivity loss, lengthy transition time, and uncertain return on investment. These reasons are echoed widely in the literature. Although it is clear that lack of health IT adoption is a critical obstacle to PBPH, our interviews also demonstrated that implementing an EHR or a registry is not sufficient for a practice to engage in population health management. Below, we focus on those challenges specific to PBPH.

Technology Issues

Among populations that adopt a registry or EHR, technology-related challenges remain. To adequately support PBPH, systems need to be user-friendly and contain robust PBPH capabilities, which lead to improved efficiencies. Some providers who were initially enthusiastic about technology spoke of how they are disappointed at their inability to use systems in the way they had envisioned. Other providers face challenges in finding systems that have the functionality they require for supporting PBPH.

For instance, most available systems do not easily generate reports, nor do they present data in a manner that can easily be applied to practice. To try to make off-the-shelf systems more compatible with their needs, some practices build their own back-end SQL reporting systems to allow them to generate reports. Unfortunately, with this additional layer of complexity, clinicians may not be able to run the reports themselves. Some providers we interviewed felt very disconnected from the “black box” from which their reports were generated. One provider mentioned that she does not feel that she has time to request a report from a central office; whereas when she had worked in a smaller practice and could generate reports on her own, she was more inclined to do so.

Systems also may not have tickler/notification systems that are easy to implement. The providers we interviewed noted the importance of alerts and reminders for ensuring patient compliance. However, if not chosen carefully, many alerts and reminders usually lead to alertfatigue, with providers ignoring what may be important information. Many providers said they would like to be able to set reminders that appear in their inboxes at a future date, designed as a tickler system, so that they are not overwhelmed with alerts about followup activities that may be months away. At the same time, providers would like an area within a patient record that summarizes the tests and services due for that patient in the near future, so that scheduling for the next appointment can occur concurrently with the patient’s visit. Providers also expressed a desire to be able to prioritize pop-up reminders according to urgency.

Some practices actively seek software that supports PBPH, but in our interviews we found that many do not. According to one expert, many clinicians view usability of technology in terms of what allows them to continue practicing medicine as it was practiced in a paper-based office. This viewpoint may impact the availability and utility of today’s products—if providers are not seeking tools needed for PBPH, vendors will not have the incentive to create tools to support these functionalities. Several panelists stated that the functionalities in the systems that vendors sell are the functionalities that customers request. Panelists noted that “enterprise customers,” such as cities or regions that represent a large number of providers, have had success in increasing the population health management functionalities offered in vendor products.

Data Issues

Clinicians are quite concerned about obtaining accurate data. At issue are three items: practices must have accurate, comprehensive data generated from within their practice that is in a usable format; practices need access to patient information that is generated from other parts of the health care system, such as laboratory and pharmacy data; and systems must be able to use data to produce standardized and meaningful reports.

Reports generated by information systems are only as good as the data that enter those systems. This data must be entered in a discrete form to support PBPH, so that the data can be searched. Many EHRs do not have data fields for important facets of PBPH. For example, one of our interviewees mentioned that EHRs are typically able to capture smoking status, but are not able to capture smoking history or such subtleties as recording that someone is a social smoker. Although this particular group worked with its vendor to create such functionality, unless there is broad consensus on the types of data fields that are important for preventive care, such fields will be introduced only piecemeal, if at all. Even if appropriate data fields exist, requiring that members of the practice record all relevant information about their patient interactions may generate an unacceptable negative impact on workflow. One provider whom we interviewed noted that it was difficult to train his care team to consistently take note of relevant pieces of information from the patient visit.

In the absence of such data sources, many practices rely on billing data to create reports or identify populations of practice. Such data are often inaccurate and fail to capture sufficient clinical information to support PBPH. For instance, a practice would be unable to use billing data to identify which of the diabetics in the group are poorly controlled.

To fully engage in PBPH, practices need to be able to obtain data from outside of their practices. Those who receive outside data on paper are burdened with manual data entry if they wish to include those data in their systems. Ideally, providers should have access to data exchange mechanisms that allow them to receive patient health information in a standardized, discrete form from laboratories, pharmacies, and other providers and to electronically incorporate this information into their patient records. Many areas in this country lack health information exchange mechanisms, making it difficult for practices to receive patient health information electronically. Even among practices that can receive information transmitted electronically, it may not be in a searchable form. While many EHRs are able to store scanned documents from other providers, the information within these saved documents cannot be searched or captured in reports.

There is a lack of standardization when it comes to generating reports and calculating performance measures. Providers are accountable to a variety of different payers, each with its own guidelines and individualized benchmarks for care. These different requirements impose a large burden on a provider needing to meet the requirements of each of its insurers. As one physician stated, “I want to see standards… rather than each insurer saying they want to look at different things. There’s a hoop for each carrier.” The absence of standardized performance measures may force providers to avoid PBPH-type care and to prioritize the allocation of resources according to the reporting required by their payers for reimbursement.

A particularly challenging issue related to tracking quality measures pertains to the denominators used to generate performance reports. First, queries need to have filters to ensure that patients who should not be included, such as those who are no longer living or those who have transferred to a different practice, are not included in the calculation of performance measures. Many of the providers we interviewed explained that systems need built-in

mechanisms, such as the integration of exception codes, to be able to exclude from calculations patients who have, for example, refused treatment. Currently there is no consensus on how these types of exception codes should be added into health IT systems, and taken into account by payers and others who use the performance data.

Another limitation is the lack of standards related to accounting for individuals for whom guidelines are inappropriate. One physician pointed out, “If you have a patient with five significant medical problems and you try to manage that patient by following the guidelines for the five chronic diseases, you’ll kill [him]!” Without the ability to make accurate calculations, providers may dismiss performance reporting as inaccurate and meaningless. Developing consensus and standards around performance reporting would help advance population management.

Reimbursement Issues

The current model of reimbursement of care creates disincentives to the practice of PBPH and the proactive management and coordination of care. Currently, care is reimbursed primarily would have to be provided without reimbursement. According to current estimates, 40 percent of the primary care workload is not reimbursed under the face-to-face fee-for-service approach to reimbursement.32 PBPH would add to this already heavy burden. A practice must cover its costs in order to remain viable. Clinicians have little choice but to provide only the care insurers consider to be important, which today does not include a PBPH approach. As one provider said, physicians “do [what] we do now because that’s the way we can survive.”

In our interviews we saw a pattern of clinicians utilizing PBPH when there are programs in place to reimburse for that care. For example, several practices are using chronic disease management systems to track patient care related to diabetes or hypertension when their payers have programs which reward that care. Others had devised systems to report the measures necessary for Medicare’s Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI). Reimbursement policies that provide incentives for proactive preventive care and disease management more broadly would make the practice of PBPH more viable.

Paradigm Shift for the Practice of Care

The movement towards PBPH requires a shift in how medicine is practiced, including changes in providers’ attitudes, workflow, and overall approach to care. As one panelist described it, “PBPH requires moving from running on the hamster wheel to proactively managing a patient panel. This wasn’t how most clinicians were trained to conceptualize their job.” This shift may be met with some resistance as providers assess the impact of making this change on their practices.

It is not hard to see how and why PBPH may be inconsistent with how providers view the practice of medicine. Clinicians are trained to treat their patient populations by providing individualized care to one patient at a time. As one provider stated, “we define our work by what is done in the exam room.” The physician-patient relationship relies heavily on the physician’s ability to develop a trusting relationship with the patient to influence health behaviors. Moving the focus from the individual to the population level constitutes a paradigm shift and may alter how providers view their relationships with their patients. As one provider commented, “population management is something that is taking our physicians a long time to understand.”

Proactively thinking about the entire population is very different from reacting to individual encounters with patients who arrive at the practice. Several of the clinicians we interviewed were uncomfortable about the implication of proactively reaching out to patients to induce them to seek appropriate care. Currently, practices see only those patients who are sufficiently committed to maintaining their health that they schedule appointments. Some clinicians expressed that they were not interested in providing care to patients who did not seek care. In addition, there was concern that the end result may be for patients to be even less accountable for their care than they are today. This shifting of responsibility from the patient to the clinician may not be a burden clinicians want to undertake, especially for those who feel strongly that this is beyond the scope of their responsibilities.

The clinicians we interviewed also expressed concern as to whether or not their practices have the capacity to expand their scope. Many feel they are working to their limits, with timeconstrained schedules, already leading to limited time with patients. There is real concern on he part of providers that PBPH will increase the need for more appointments than their chedules can accommodate.

Adopting PBPH, especially if the use of new technology is involved, has an impact on workflow. For example, rather than relying on dictation of notes following a patient visit, relevant data must be entered into discrete fields in an EHR or a registry for it to be queried and used for population health management. As one physician interviewee commented, “Physicians preferred the EMRs that looked and acted like old paper charts, but [those EMRs] couldn’t manage datasets very well.” The loss of productivity as workflows are adjusted and providers learn new techniques is another concern.

Finally, collecting and documenting data on the patient population represents a significant time burden for physicians and can, as one provider stated, “detract from your ability to care for someone.” Some of the providers we interviewed recommended that health IT systems be developed with enough simplicity so that others within the practice are able to query the system and engage in PBPH. If providers are able to delegate query tasks, it may reduce the time and burden associated with implementing PBPH.

Leveraging Policies to Address Challenges

The project experts noted several opportunities to address some of the above challenges and increase the adoption of PBPH. In particular, they discussed how PBPH could be incorporated into important policy initiatives related to health care reform, ARRA, and initiatives to strengthen the primary care workforce.

Health Care Reform

Proposed efforts to reform the country’s health care system and provide insurance for a greater number of individuals elevate the importance of re-examining the way primary care services are reimbursed. Reimbursement systems with a greater emphasis on outcomes may incentivize practices to devote additional resources to and more fully engage in PBPH. If providers are more motivated to proactively provide preventive care and disease management services, they may be more likely to demand applications with this functionality. This, in turn, may give IT vendors the incentive to develop such programs. Models like PCMH, which has substantial overlap with PBPH, may also be incentivized in health care reform efforts. This may help support many of the components of proactive population management.

Many of our experts noted that an incremental approach to payment reform may be preferable. It may be appropriate, therefore, to implement rewards for providers who demonstrate that they are performing some population management tasks—like the functionalities outlined here. This could serve as a first step towards payment based on health outcomes.

Health care reform may also smooth the way for PBPH by establishing a uniform set of performance measures. Clarification about what types of measures should be included in a PBPH application will make it easier for vendors to tailor products to the needs of primary care practices. There is already some precedent, on a local level, for this type of harmonization of performance standards. For example, as part of the Quality Health First Initiative, the Indiana Health Information Exchange (IHIE) and a coalition of local employers convened employers, insurers, providers, and other stakeholders to develop a consensus set of quality measures. IHIE generates reports on these measures and disseminates them to participating clinicians.

Addressing concerns about inconsistent measures could make PBPH easier for vendors designing products and reduce provider resistance by distilling population-level data into a set of reports that contain, in one place, all the tracking information necessary for the full panel of patients.

A final benefit from health care reform might be establishing a larger role for patients in their own care. One of our experts explained that involving patients with managing their personal health records allowed them to prevent errors, particularly with medication management. More actively engaged patients may help practices to develop a more comprehensive picture of their patients, which is a key requisite for successful population management.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)

Under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Federal Government is investing unprecedented resources into health information technology. A significant portion of this funding—approximately $36 billion—will be used to provide incentive payments to providers who demonstrate “meaningful use” of EHRs. Approximately $2 billion will be allocated to training providers through regional extension centers. By providing incentives to Medicare and Medicaid providers who demonstrate “meaningful use” of EHRs, ARRA will likely boost health IT adoption. PBPH could most directly be supported by this legislation if the functionalities established as part of this project are incorporated into the meaningful use criteria. As described above, some of the concepts related to PBPH are supported in the initial recommendations for the definition of meaningful use, but the operationalization of those concepts is not yet clear. While it would be optimal to incorporate all functionalities into any new standards that emerge from ARRA, inclusion of a portion would still increase the population health capabilities of future systems.

Another benefit of ARRA that is relevant to PBPH is the potential to increase the amount of information available in electronic form. If more practices adopt EHRs in order to receive the incentive payments, more data will be stored in discrete forms. In addition, ARRA provides support for health information exchange. This could facilitate the collection of data from other providers and parts of the health care system. This additional information is vitally important for practices trying to manage their patient populations.

Finally, ARRA could also promote PBPH through the provision of training to help providers engage in PBPH. The legislation includes funding for extension centers and training grants to support the implementation of health IT. Our interviews with providers suggest that many will require additional training to take advantage of the population management functions in their systems. On several occasions, we spoke with two individuals from the same practice and each had a different understanding of which functionalities could be performed in their system. It is likely that many providers are not using their current systems to the fullest capacity.

ARRA may provide some opportunities for increased training in the use of health IT to support population management, but workforce development may require investment of resources beyond what is available through ARRA. Physicians, nurses, and others in the primary care workforce who are new to EHRs may require training to effectively use those systems. Even among providers who have adopted an EHR, additional assistance may be needed to enable them to create and interpret reports on their patient populations. They will need to understand how to turn population data into information that can inform practice decisions related to such issues as staffing needs and performance improvement. Training may be required to help providers to capture data efficiently and to use such features as exception codes. Technical assistance may also support the integration of PBPH tools into practice workflows. Additionally, medical and nursing schools could help address one of the other challenges to PBPH—clinician culture. Education and training programs could help providers to adopt a more population-focused orientation. To support this shift in training, it may be necessary to develop PBPH competencies to guide the development of curricula and accreditation exams.

Next Steps

In addition to helping identify the policy opportunities described above, experts offered recommendations for additional research and dissemination to better promote PBPH.

Additional Research

One way to increase the uptake of PBPH is to develop systems that have the potential to be time-savers for primary care providers. Applying clinical decision support (CDS) mechanisms to population health data could automate some processes related to preventive care and disease management services. PBPH systems could not only remind providers and patients about upcoming needs, but could also generate the orders for the required tests. Designing products that have demonstrated value to providers—in both improved outcomes and increased efficiency—is a key to encouraging the spread of PBPH.

Some clinicians may prefer systems that allow them to dictate their notes into an EHR. Whilea great deal of research has been done in the area of natural language processing, further research is needed to effectively convert text into discrete data elements. A greater challenge—one that may call for both technical improvements and new workflows—is to allow those dictated data elements to enter a system in real time so that they can be used to fuel CDS during a given visit.

One potential area for research would be to determine how to make the best use of “messy” data. In addition to trying to make systems that facilitate accurate and complete entry of data, it may be worth determining how to make the most of data that are imperfect. This may entail developing protocols that assess the accuracy of data from different sources and place greater weight on data deemed to be more reliable. Furthermore, a better understanding of the sources of data inaccuracy could inform the development of technology that reduces the likelihood of errors.

A different approach to PBPH-related research would be to gain a better understanding of how practices are able to successfully implement some or all of the functionalities. Through interviews with a variety of providers, we were able to gather some examples of practices that are managing their patient population. However, the interviews were brief and did not allow us to explore more fully how those functionalities are being performed. It might be valuable to conduct a series of case studies to develop a more complete picture of the methods practices are using to engage in PBPH, the obstacles they face, and their techniques for overcoming them. As part of such an effort, a public repository of examples of PBPH reports and techniques that work well could be developed and used to help providers build on the success of other practices’ experiences. In examining PBPH implementations, it would also be valuable to investigate the impact of the functionalities on the efficiency of care delivery and on health outcomes.

Additional research needs include developing a better understanding of the types of data fields and reports that are necessary to support PBPH. As discussed above, the functionalities developed through this effort highlight the ways in which providers should be able to manipulate data to make it actionable. Yet, this project does not provide a list of the specific types of fields that are particularly relevant for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. As a followup to this study, clinicians and experts could be consulted to compile a specific list of the data elements that would be important to support a variety of aspects of preventive care, ranging from diabetes management to smoking cessation.

Dissemination

Dissemination of this project’s findings is essential to translate them into practice and, ultimately, to influence and support the transformation of primary care delivery. Successful translation from the current recommended functionalities to primary care providers’ offices is predicated on marketing the concept to multiple audiences. The experts identified key issues and audiences who will be critical in increasing the uptake of PBPH. First, the concept of PBPH must be introduced among primary care providers, health IT vendors, educators, policymakers, and third-party payers. Second, the functionalities required for optimal implementation of PBPH need further vetting and refinement among primary care providers and health IT vendors. This could include vetting the revised version of the functionalities presented here with a larger number of providers and adding additional technical specifications in order to make the functionalities more specific for health IT vendors. Third, educators need to be acquainted with PBPH concepts, including opportunities for and barriers to implementation, to develop PBPH education and training that incorporates the use of PBPH in primary care practice.

CONCLUSION

The technology to support a shift from “hamster health care” to proactive population management is part of a larger transformation of primary care. Although some primary care providers are beginning to adopt a proactive, panel-based approach to care, primary care in the U.S. has not yet undergone this paradigm shift. While not sufficient, health IT tools are necessary for conducting PBPH. There is currently a paucity of effective, usable tools to support a population health approach to primary care. This report outlined the key IT functionalities for PBPH, developed from the perspective of providers.

Defining these functionalities is an important step towards greater adoption of PBPH, but many challenges remain. While the adoption of PBPH, as defined in this report, has the potential to improve the quality, efficiency, and effectiveness of primary care delivery, implementation of this approach will require broader changes to the way health care is delivered in this country, including changes in reimbursement systems, data accuracy and availability, and provider culture and training. Providers currently lack the incentive to pursue a proactive, population-based approach to care, given the limitations of the existing reimbursement system. As long as there is limited demand from providers, it is unlikely that vendors will develop the appropriate tools or that consensus will be established on the specific algorithms and data fields necessary for PBPH. Funding for pilot projects to support the development of tools designed by clinicians for clinicians is warranted. As technology evolves, products will incorporate features that will make tools both easier to use and more valuable to providers.

ARRA and pending health care reform legislation offer tremendous opportunities to support the transformation of primary care. The definition of meaningful use for the ARRA incentives is still under discussion. While components of PBPH are included in preliminary recommendations to the National Coordinator, more explicit consideration of objectives to encourage population based care may be warranted. Significant funding from ARRA has been devoted to training providers through regional extension centers. Targeted PBPH training for the health care and health IT workforce will empower providers to better use existing tools and become more savvy consumers. Health reform legislation may also offer opportunities to promote PBPH, especially if restructuring reimbursement for primary care is a critical component of reform.

As training and technology to support a population health approach to primary care become more available and incentives are established to foster this type of care, PBPH may become a more widely viable option for primary care providers. Such advances will help PBPH contribute to transforming primary care and to improving health care quality, patient health, provider 3satisfaction, and the efficiency of the health care system.

# # #

Chapter 8 contains examples of Population Health Management including:

–Indian Health Service: iCare

–Washington State Department of Health: Chronic Disease Electronic Management System.

–Vermont Department of Health: DocSite

–New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Primary Care Information

–Project: eClinical Works

–Kaiser Permanente

–Mayo Clinic

–Community-Based Practices