NCVHS Concept Paper Looks How to Achieve the

Promise of Health Reform and Electronic Health Records

The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) met June 16-17, 2010 in Washington, DC, and used the NCVHS concept paper “Toward Enhanced Information Capacities for Health” as the basis of discussions for their 6oth Anniversary Symposium of the committee. The paper, issued May 26, 2010, focuses on policies HHS could establish to maximize the benefits that could be acheived through the appropriate use of the tremendous amount of health data that will be generated with Electronic Health Records.

The committee advises the Secretary of HHS on policies toward health data, statistics, privacy, national health information policy, and Administrative Simplication of HIPAA.

NCVHS Concept Paper

“Toward Enhanced Information Capabilities for Health”

PDF FORMAT

The text of the 11-page paper is reproduced in whole below.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYHealth care reform and federal stimulus legislation have created an unprecedented opportunity to improve health and health care in the United States. The nation’s ability to seize this opportunity will depend greatly on the existence of robust health information capacities. The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) is the statutory advisory body on health information policy to the Department of Health and Human Services. On the occasion of the Committee’s 60th anniversary, this concept paper outlines its current thinking about the necessary information capacities and how NCVHS can help the Department guide their development.

We are entering a new chapter in the health and health care of Americans. The expansion of health care coverage, the infusion of new funds and adoption of standards for electronic health records (EHRs), and increased administrative simplification offer us the potential to use the enriched data generated to better address our country’s health and health care challenges. Having better information with which to measure and understand the processes, episodes, and outcomes of care as well as the determinants of health can bring considerable health benefits, not only to individuals but also to the population as a whole.

To be able to achieve the promise of these new developments, we need to be attentive to the underpinnings of the data, ensuring that they are easy to generate and use at the front lines as well as easy to reuse, manipulate, link, and learn from within a mantle of privacy and security. It is important to remember that the new data sources are not necessarily a replacement for traditional sources such as administrative and survey data, which play a key role in our infrastructure. Rather, the new sources present an opportunity to augment and enrich traditional sources. While efficiency may be gained by replacing some survey and administrative data with newer EHR data, we must continue to nourish and sustain the traditional data sources that offer unique and irreplaceable information for both clinical and population health purposes.

National health information capacities must enable not just better clinical care but also population health and the many synergies between the two. More specifically, health information policy should foster improved access to affordable, efficient, quality health care; enhanced clinical care delivery; greater patient safety; empowered and engaged patients and consumers; patient trust in the protection of their health information; continuous improvement in population health and the elimination of health disparities; and support of clinical and health services research. A major priority of health information policy should be to enable the multiple uses of data, drawn from the full range of sources, while minimizing burden. Most sources have primary uses for which they were designed; however, with adequate standardization, privacy protections, and technology, the data from many sources can be used for multiple purposes. Realizing the collective potential of all information sources is what will allow the U.S. to maximize the return on its investments in system reform and health IT for the benefit of all Americans.

As information capacities expand, it is critical that the information be comprehensive, timely, efficiently retrievable, and usable, with full individual privacy protections in place. “Comprehensive” refers to the inclusion not just of traditional health-related data, but also of data on the full array of determinants of health, including community attributes and cultural context. Usability of the data—whether for initial use or reuse―requires a well-coordinated effort to assure the accessibility and availability of information as well as its standardization.

NCVHS will continue to use its consultative and deliberative processes, working collaboratively with other HHS advisory committees, to help the Department meet these opportunities and challenges. Given the rapidity of the changes now under way, we cannot over-emphasize the urgency of this endeavor and the need to move ahead with deliberate speed.

INTRODUCTION

Health care reform and federal stimulus legislation have created an unprecedented opportunity to improve health and health care in the United States. The nation’s ability to seize this opportunity will depend greatly on the existence of robust health information capacities. 1 To maximize the return on these enormous investments and make it possible to evaluate their impact, health information capacities must be carefully developed with an eye to their uses for improving health care and health for all Americans. New investments in EHRs and health information exchanges are important contributors, especially for clinical care, but the benefits from these investments will be limited unless the synergies with other types of health information are recognized and used. Population-level data from vital statistics systems, surveys, and public health surveillance and health care administrative data are equally important information sources. Assuring that all these sources are adequately developed and supported and can be integrated appropriately is essential to developing the information capacities the nation needs.

The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics, the Department’s statutory advisory body on health information policy, has long assisted the Department in the development of national health information policy, providing thought leadership and expert advice in the areas of population health, privacy, standards, the NHII/NHIN, health care quality, and more. Nearly ten years ago, NCVHS put forward a vision for a national health information infrastructure in its 2001 report, Information for Health,2 followed in 2002 by a vision for 21st century health statistics.3 Today, as data and communication capacities explode and health care coverage expands, new thinking and visioning are needed to clarify the information capacities that will make it possible to meet our national goals for better health and health care for all Americans. On the occasion of the Committee’s 60th anniversary, this concept paper outlines its current thinking about the required capacities and their development.

In 2009, as course-altering legislation was unfolding, NCVHS began to consider how it could assist the Department’s development of the necessary information capacities.4 All four NCVHS subcommittees have contributed to the early thinking on this subject, and all plan further work

—————————————————————————-

1 We use the term capacities in the sense of the ability to perform or produce. That is, information capacities are understood in relation to specific needs, purposes, and functions of information.

2 NCVHS, Information for Health: A Strategy for Building the National Health Information Infrastructure, November 2001.

3 NCVHS, Shaping a Health Statistics Vision for the 21st Century, November 2002.

4 As part of this process, NCVHS in 2009 commissioned two authors of the 2002 health statistics vision report to help the Committee consolidate and update its recommendations. Their report to the Committee is posted on the NCVHS website. < http://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/090922p3.pdf >

————————————————————————————-

in their respective domains, as described below. 5 The Committee has crafted a highly effective process for bringing multiple points of view and areas of expertise to bear as it develops recommendations to the Secretary, and this process is well suited to the work that lies ahead. NCVHS will continue to use its consultative process to create venues for dialog, eliciting input and perspectives from stakeholders and experts regarding critical challenges, potential opportunities, and next steps. It will use this external input and its own broad expertise to help the Department develop health information policies that are commensurate with new opportunities and needs. Given the rapidity of the changes now under way, we cannot over- emphasize the urgency of this endeavor and the need to move ahead with deliberate speed.

INFORMATION CAPACITIES FOR HEALTH AND HEALTH CAREPublic sector involvement in health information has a long history. State, local, and federal agencies have gathered information through vital records, hospital and ambulatory data sets, public health surveillance, population surveys, and other sources to monitor health trends, identify threats, and guide interventions to protect and promote health. Congress initiated a new type of government involvement in 1996 when the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) recognized the importance of protecting individuals’ health care information while improving the efficiency of health care delivery through standardized electronic administrative transactions. Most recently, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) began another type of intervention, providing financial incentives for health IT adoption in the nation’s hospitals and physician offices as well as funding for infrastructure support.

While much current attention is focused on the ARRA funding of health IT and critical associated tasks such as defining and implementing “meaningful use” of EHRs, a broader perspective is required to take full advantage of evolving opportunities. Widespread use of optimally configured, standardized EHRs will greatly expand the information available on health care services, users, and providers. However, promoting the health and wellness of the population also requires information about those who have not received health care services, among other things, as well as information on other determinants of health beyond traditional health care, including environmental, social, and economic factors.6

In short, national health information capacities must support a broad array of uses and purposes that include improving access to affordable and efficient quality health care, supporting clinicians in delivering care, empowering and engaging patients and consumers in their care,

—————————————————————————-

5 At present, NCVHS has subcommittees on population health, standards, quality, and privacy/confidentiality/security.

6 See the NCVHS-developed graphic of the determinants of health on page 9 of its report on a vision for 21st century health statistics (see note 3).

—————————————————————————-

ensuring patient safety, promoting patient trust, eliminating health disparities, monitoring and improving population health, and supporting health services and clinical research. As these capacities are developed, it is critical that the information being collected be comprehensive, timely, efficiently retrievable, and usable, and that individual privacy be protected.

In the Committee’s view, this requires a well-coordinated effort that assures the following:

1. Accessibility and availability of information. The availability of sufficient, timely information from relevant sources must be assured to meet the priority needs of diverse users (including clinicians, consumers, purchasers, payors, researchers, public health officials, regulators, and policymakers) for taking action and evaluating outcomes. To minimize burden, wherever possible data should be collected once, for multiple appropriate uses by authorized users. Where appropriate, the capacity to connect data from multiple sources should be provided.

2. Standardization. Standardization is necessary to enable interoperability for the efficient collection and timely sharing of information among all types of users. Robust standards should be assured through the definition, application, and adoption of terminologies, codes, and messaging in the areas of reimbursement, public health, regulation, statistical use, clinical use, e-prescribing, and clinical documents.

3. Privacy, confidentiality, and security protections. With the increasing adoption of interoperable electronic health records technology, along with the move toward global access to health data and emerging new uses of data, methods of access and information availability raise significant new and unique privacy and security concerns. Appropriate privacy, confidentiality, and security protections; data stewardship; governance; and an understanding of shared responsibility for the proper collection, management, sharing, and use of health data are critical to addressing these concerns.

Each is briefly discussed below.

1. ACCESSIBILITY AND AVAILABILITY OF INFORMATION

In today’s world, the boundaries between health care, population health, and even individual personal health management are permeable, and information exchange is increasingly multi- directional. The domains traditionally called “public health” and “health care” are increasingly intertwined, often sharing broad, common information sources and capacities. For example, promoting the health and wellness of individuals and the population requires attention to health determinants including not only the treatment and prevention of disease and the nature of community health resources but also environmental, housing, educational, nutritional, economic, and other influences. Continuously improving the quality, value, and safety of health care involves, among other things, research and knowledge management, meaningful performance measurement, education and workforce development, and support for personal and family health management. Finally, improving health and health care on a national scale requires monitoring and eliminating health disparities and assessing the health status of all Americans, including vulnerable sub-populations.

A major priority of health information policy should be to facilitate these interconnections and enable the multiple uses of information for current and emerging data needs. With health IT, complemented by the necessary privacy protections and data stewardship and facilitated by well designed standards, data can be combined to create richer information and used to address a broad array of current and emerging health and health care issues. Realizing the collective potential of all information sources is what will allow the U.S. to maximize the return on its investments in system reform and health IT for the benefit of all Americans.

At present, the major sources of data on health are:

Surveys (interview and examination) and Censuses Public health surveillance data (e.g., notifiable disease reporting, medical device reporting) Health care data (EHRs, HIEs, registries, and other such as prescription history, labs, imaging)

Administrative data (claims, hospital discharge data, vital records)

Research data (community-based studies, clinical trials, research data repositories)

Another essential set of sources for understanding health is the information on influences on health (including transportation, housing, air and water quality, land use, education, and economic factors) managed by various public and private sector agencies. In addition to all these well-established sources, new ones such as personal health records and computerized personal health monitoring devices are emerging with the potential to contribute to understanding health at individual and population levels. Social networking content has the potential to provide yet another new and novel resource.

Most data sources have primary uses for which they were designed. However, given adequate standardization, privacy protections, and informatics technology, these sources have great potential to be used for multiple purposes. For example, EHR data elements are collected to document and manage clinical care, but also can be used for public health reporting (such as communicable diseases and medication safety) and to evaluate population health and conduct health services research. Surveys are principally for population-level analysis, but survey information also contributes to clinical care. Vital records not only provide information about births and deaths, but also serve as the “bookends” of population health data. Administrative data (ICD-9-CM disease codes and CPT-4/HCPS procedure codes) were initially used for management and reimbursement, but today play a critical role in quality assessment and public health monitoring (e.g., quality and safety indicators and disease prevalence evaluation). As we look to the future, the goal is to leverage all these sources, when appropriate, and expand their utility for understanding personal and population health and their determinants while carefully protecting the confidentiality of the data they contain.

To bring about the needed improvements and efficiencies and draw all possible benefit from the large and growing investment in health IT, the emerging information capacities must enable both more effective and cost-effective clinical services and population health promotion, and their many synergies. This can be facilitated through multi-directional data sharing and linkages to generate information that is comprehensive and broadly representative. It will be critical to break down the silos that now make it difficult to share and connect data. This requires addressing the policy, institutional, technical, and other barriers that contribute to the existing silos. A workforce trained to take advantage of the broader data and informatics capacities is also essential. Detailed local data are needed to enable understanding of health and health care at local neighborhood, community, sub-population, and other levels of aggregation. Key decisions about health and health care are made at the local level, and we envision the potential to meet these needs in ways not previously possible. Finally, a critical use of population health data, especially with the advent of health care reform, is to assess the effectiveness, comparative effectiveness, and equity of health care.

Because resources are limited and burden must be minimized, information policy must set priorities regarding which data are most important in order to target investments in data collection. As noted, burden can be minimized by collecting data once for multiple uses. At least in the near term, provided that data can be put in the hands of trusted stewards, enhanced administrative data may be a powerful component that reduces the burden of multiple collections. As new capacities come on line, it may be possible to curtail or redirect some current collection activities.

An important criterion is that information, whatever its source, must be meaningful to users. Experience has demonstrated that having relevant data and information available does not ensure that it is accessible in a timely manner and useful form to the full range of potential users. Delays may be created by approval processes or regulatory requirements, as well as by the lack of data handling and analysis capacities that could enable a user to pose a question, indentify relevant data sources, and request a report that is understandable and protects the privacy of data sources. Ensuring access to useful information is a critical part of the challenge. An overarching goal of all these endeavors is to assure that data can be converted into information and ultimately into knowledge that can answer the priority questions about personal and population health in the U.S. and enable effective decisions and actions to improve them.

2. STANDARDS FOR INTEROPERABILITY, USABILITY, QUALITY, SAFETY, AND EFFICIENCY

The purposes of health information standards are to ensure the efficient, secure, safe, and effective delivery of high quality health care and population health services; to support the information exchange needs of health care, public health, and research; and to empower consumers to improve their health.

The impending implementation of the next generation of HIPAA standards, the enactment of The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in 2009, and the recent signing of health reform into law are creating an unprecedented convergence of driving forces, foundational components, technology advances and capabilities, and regulatory requirements. Together, these assets can help create a common national pathway toward achieving the vision and policy priorities of a 21st century health system that relies on a strong health information and health information technology foundation. The past five years have seen a remarkable transformation in the adoption and use of standards for electronic exchange of health information. The transformation encompasses privacy and security standards, standards for administrative and financial transactions, the establishment of unique identifiers, and more recently the adoption of standards for codifying, packaging, and transmitting clinical information between and across health care organizations. This rapidly evolving transformation is moving us closer to the ideal of a fully interoperable electronic health information collection and exchange environment that supports all functions and needs of the country’s health and health care ecosystem, as discussed in the previous pages.

Data standards provide a key architectural building block that supports the collection, use, and exchange of health information. Health information standards have been developed and are being adopted and implemented in many different areas. Capturing information in codified format through standard representations such as clinical vocabularies and terminologies, code sets, classification systems, and definitions is a key strategy for achieving semantic interoperability. The inclusion of standardized metadata, which describe characteristics of the data such as provenance, increases the potential for assessing the reliability and validity of the data for aggregation, research, and other uses. Organizing and packaging data through defined electronic message and document standards to be accessed and exchanged via standardized electronic transport mechanisms and protocols achieves access and exchange of health information. The availability and integrity of health information is protected and ensured through the deployment of security standards, thus guaranteeing confidentiality and privacy of protected health information. Finally, the certification of health information technology for Meaningful Use depends on the wise deployment and use of health information standards.

3. PRIVACY, CONFIDENTIALITY, SECURITY

With the move toward the management of health data in electronic form, there is a significant opportunity to enhance health data access, utility in patient care, and important secondary uses. The opportunity is further enhanced through the emergence of new methods to exchange health data, both on a regional and national basis. However, the ability to realize the potential of electronic health data depends greatly on ensuring that uses are appropriate and individuals’ reasonable privacy, confidentiality, and security expectations are met.

Individuals should have the right to understand how their health data may be used, and to provide consent where appropriate. Often, consent is difficult, as not all uses are known at the time the health data are collected. Further, standards do not yet exist to track an individual’s consent as data are exchanged. Although many of the population health uses described in this concept paper involve aggregated or de-identified health data, legitimate concerns exist about group harms and possible re-identification. In addition, the possibility of using health data from emerging information sources, such as personal health record systems, raises unique privacy concerns.

NCVHS has discussed many of these privacy challenges in numerous reports and letters to the Secretary. Most notably, NCVHS published two reports, a Primer on health data stewardship 7 and Recommendations on Privacy and Confidentiality, 2006-2008. Both are available on the NVCHS website.8

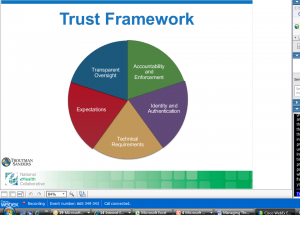

Further work is necessary to develop the privacy, confidentiality, and security standards that should apply as these data uses continue to evolve. In addition, work is needed to establish governance structures to provide the proper oversight of entities that exchange and use health data. In essence, governance is the accountability for ensuring that proper data stewardship (as described in the NCVHS Primer cited above) is practiced. To differentiate between governance and data stewardship, data stewardship is focused on the internal practices of the entity that uses health data, whereas governance is focused on the oversight of such entities to ensure that their data stewardship practices are adequate. Such oversight includes initially approving entities that have access to data, ensuring that such entities appropriately use and protect data, and ensuring that entities that misuse data are appropriately sanctioned.

THE WAY FORWARDTaken together, today’s emerging policy opportunities and the nation’s longstanding health challenges create a situation of considerable urgency for the United States. The openness to bold new approaches offered by recent legislation will disappear quickly. Given that the U.S. lags behind most other industrialized countries in the health status of its citizens, we must seize the opportunities to maximize the health benefits and begin to assess whether the huge investments are indeed having the desired impact.

This paper has noted the critical federal role in devising health information policy to support national health goals. Federal leadership is more needed than ever to create the comprehensive approaches that will guide the development of information capacities and coordinate efforts by actors in the public and private sectors. Whatever progress is made in the critical transition to electronic health records, clinical data alone will not suffice; broad information capacities that

————————————————————

7 An NCVHS Primer: Health Data Stewardship―What, Why, Who, How, December 2009.

8 http://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov

————————————————————

draw on all the sources and serve all the purposes discussed in this paper will be necessary. This will require shoring up the data resources for public functions such as surveys, safety surveillance, and vital records, along with strategic thinking to determine what capacities will be needed in the future and how to guide their development. Many issues require research and demonstration as part of a prioritized, adequately funded research agenda. In addition, further investments in a trained workforce are needed, to ensure the availability of professionals and leaders who can properly use information resources for analysis and decision-making.

As it develops policies and strategies, the Department has always invited input from experts and stakeholders; and NCVHS has long helped to facilitate this dialogue and distill the key messages and lessons. NCVHS will continue to use its consultative and deliberative processes, working collaboratively with other HHS advisory committees, to help the Department meet the current opportunities and challenges. As noted, all NCVHS subcommittees plan to be involved in this effort; this report is an early installment on subcommittee and full Committee work plans for the coming 18 months or more. NCVHS expects to develop recommendations on a research agenda, which may be the focus of one or more hearings. Each of the subcommittees is identifying the key issues in its domain, to be pursued through workshops, hearings, and internal deliberations as NCVHS develops recommendations for the Secretary. The subcommittees’ preliminary thinking is outlined below.

SUBCOMMITTEE ON QUALITY

Over the next two years, the NCVHS Subcommittee on Quality will focus on supporting the development of meaningful measures, leveraging both existing and emerging data sources (e.g., patient-generated data, remote monitoring, personal health records), and in particular identifying significant opportunities and gaps. Critical to meaningful measurement is the availability of relevant data elements that could be easily captured using certified EHR technology and functionality, among other tools. The Subcommittee on Quality will identify emerging health data needs for a health system where the individual engages in his or her health and health care. As a near-term priority, the Subcommittee will address the data needs of person-centered health and health care, emphasizing coordination and continuity of care across a continuum of services. A longer term goal is to develop a national strategy to leverage clinically rich health data to address important national questions about determinants of health and disease.

SUBCOMMITTEE ON PRIVACY, CONFIDENTIALITY AND SECURITY

The NCVHS Subcommittee on Privacy, Confidentiality and Security will focus its efforts on providing recommendations that support national priorities, in coordination with such groups as the ONC HIT Policy Committee’s Privacy and Security Workgroup. In the next year, the Subcommittee plans to develop recommendations regarding governance as well as a framework for the identification and appropriate management of sensitive data. The Subcommittee will also consider transparency and the role of patient consent. In addition, it will continue to review and make recommendations regarding new privacy, confidentiality, and security regulations; compliance with these regulations; and strategies for effective enforcement.

SUBCOMMITTEE ON STANDARDS

Health care reform legislation now provides a new opportunity to continue the administrative simplification that began under HIPAA―a process in which NCVHS will remain heavily involved. The NCVHS Subcommittee on Standards will continue to meet its responsibilities related to HIPAA; will implement the many administrative simplification responsibilities assigned by the Health Reform Act of 2010; and will meet new requests for recommendations on the use of standards to enhance interoperability of the transmission and semantics of health data as they arise. As we look to the future, several goals stand out with respect to standards. The Subcommittee will seek to ensure a comprehensive framework and roadmap for health information standards that support the national health IT strategic framework, vision and policy priorities; the public health policy agenda; the NCVHS proposed data stewardship framework; a national research agenda that includes comparative effectiveness; and the needs of all data users.

SUBCOMMITTEE ON POPULATION HEALTH

Understanding the population’s health and its determinants relies on multiple data sources, including population surveys, clinical data, administrative data (notably, birth and death records and billing data on use of health services), and public health and environmental reporting systems. At the national level, Federal agencies such as the National Center for Health Statistics are charged with developing methods, assessing validity, and reporting national population health information. As we envision building a comparable capacity for communities and states across America, the quality of information and its timeliness will be central to success. The Subcommittee on Population Health will focus on facilitators and barriers to data linkage at state and local levels as a critical part of health information infrastructure, specifically linking EHR data with existing administrative and local survey data. Fundamental to understanding population health is describing the underlying population, which also comprises those who have not seen a doctor recently or have refused to respond to a survey. The work of the Subcommittee will focus on methods to ensure that linked data sources provide valid health information, including methods to adjust for missing data and methods to protect privacy.